Hard as it may now be to imagine but, a century ago jazz was a wild, untamed music fresh off the boat from America. Hated by conservatives, loved by youths; both the soundtrack to wild clubbing and a sonic siren for modernism, jazz meant many things – not least that the UK would spend the rest of the century following developments in African American music.

What kind of reception did those black American musicians get when they came to the UK? This isn’t a question often asked – UK pop/ rock histories love to go on about Jimi Hendrix being welcomed here at a time when Americans didn’t recognize his genius, and old Mississippi blues men settling in Yorkshire because it was so much more welcoming than the Jim Crow South. When this is stated, there is often a collective outbreak of patting ourselves on the back for not being racists – at least towards musicians we like – unlike our cousins across the Atlantic. But that was 50 years ago. How about a century ago?

“Fascination and fear sums it up well,” says Professor Catherine Tackley when asked about how Edwardian England responded to the inclux of jazz musicians.“There was certainly a strong novelty element, and jazz being understood as black music certainly established it for some as a threat. There was overt racism expressed, particularly towards members of black theatre companies which was also tied up with oppositions to ‘Alien’ workers more widely.”

Tackley is Head of Music at the University of Liverpool and curator of an exhibition that opened late-January in London. Rhythm & Reaction: The Age of Jazz in Britain looks, at first glance, to be just another gathering of old artifacts from a bygone age. And yet while this exhibition may trade in arcane items from a sepia era, Rhythm & Reaction provides both a fascinating overview of a largely forgotten time and a history lesson: documented here is how a new American sound, created by pioneering black musicians, would go on to resonate across Britain.

The exhibition emphasises how, almost a century ago, the “jazz age” – as F. Scott Fitzgerald famously described a post-WW1 USA, overflowing with money, confidence and hot music – also existed in the UK. Admittedly, in a nation traumatized by the war, Britain’s jazz age was never going to be as loud and ostentatious as that then underway in the US. But what Rhythm & Reaction makes evident is how jazz inspired an outbreak of British creativity – not just music making but painting, graphic design, fashion, journalism, textiles, even ceramicists responded to the sound of New Orleans.

Using the end of WW1 as a starting point, the exhibition begins by acknowledging earlier African American musicians who had performed in Britain. In 1873 the Fisk Jubilee Singers toured widely to raise funds for a black university in Tennessee (and sang for Queen Victoria: her Royal Highness was impressed) while minstrels worked the music hall circuit from the 1870s on and would remain popular up into the post-WW2 years (so much so they inspired the now infamous Black & White Minstrels TV series). Ragtime arrived in England just before WW1 and fed into a craze for American dances such as the Lindy Hop and the Grizzly (swing dance’s origins are here). But jazz, unlike the aforementioned genres, launched a cultural revolution.

Jazz detonated in London in 1919 with the arrival of The Original Dixieland Jass Band – a crude, if energetic and entertaining, white quintet. The ODJB resonated with British youths in a manner comparable to the arrival of Elvis in the 1950s, Jimi Hendrix in the 1960s, The Ramones in the 1970s and Run-DMC in the 1980s. Raw American music, often involving more energy than skill, excited and inspired British youths (while upsetting their elders) across the 20th Century.

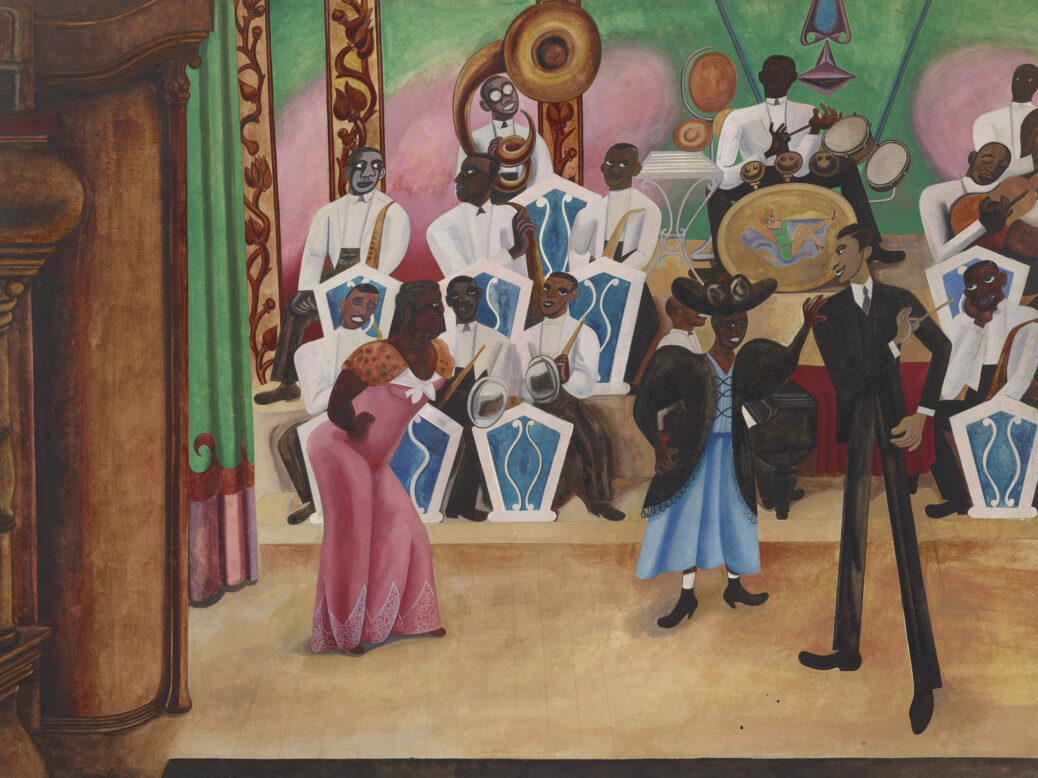

Featuring striking paintings by William Patrick Roberts and Edward Burra alongside exceptional graphic and textile work, Tackley’s exhibition makes a case for jazz being at the forefront of British modernism. The jazz musicians may have paid little or no attention to developments in painting and literature, but they fired up all kinds of creative possibilities here.

British youths instinctively responded to these energies, and in Edwardian society jazz’s spontaneity and insouciance became indelibly linked to sex. Inevitably, race came into play in an era where the UK was predominantly white and a colonial mentality shaped through centuries of Empire meant people with dark skins were often treated as inferior. Sex and race have often proved an explosive combination, as reflected by a selection of paintings and cartoons featured by Rhythm & Reaction. These range from crude caricatures of musicians as savages, through to Scottish artist J.B. Souter’s painting The Breakdown. The Breakdown featured in the Royal Academy’s 1926 Summer Exhibition and, in portraying a naked white woman dancing to a fully clothed black saxophonist (who sits on a broken classical bust), immediately proved controversial: Edgar Jackson, the editor of Melody Maker (the first UK magazine devoted to jazz), decried the painting, but not because of its toxic racism. Instead, Jackson stated, “We demand also that the habit of associating our music with the primitive and barbarous negro derivation shall cease forthwith”.

Jackson campaigned for jazz to be seen as a sophisticated Anglo-Saxon music. The aptly named Paul Whiteman – a white American bandleader who played symphonic jazz, ie jazz softened with elements of light classical music – was its exemplar and very popular in the 1920s. But there was no hiding that the musical geniuses pushing jazz forth were the likes of Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, both of whom began touring the UK in the early 1930s. Not that they were welcomed by all: Armstrong’s London debut found The Daily Herald’s critic writing of the man who would touch more lives than almost any other 20th Century musician, “He looks and behaves like an untrained gorilla”.

“Stereotype was never far away,” says Tackley, “and the point I make is that this can be traced back to the exaggerated portrayals in minstrelsy. There was an impulse to ‘civilise’ ‘primitive’ jazz via dance music, but then in the 1930s particularly, a growing realisation that individual improvisation by black musicians was a key aspect of the music. Black musicians generally seem to have been welcomed here. That review of Armstrong is extreme, and he does seem to have been more problematic for British audiences than Ellington, because the latter fitted better with dance bands on stage and dance halls.”

Indeed, Rhythm & Reaction doesn’t dwell on the negative, instead offering insight into how black musicians, increasingly from Britain’s Caribbean colonies, came to win loyal audiences here. Striking photos of Ken “Snakehips” Johnson – who lead the first all black British jazz band until a Luftwaffe bomb killed him on the bandstand of London’s Café du Paris in 1941 – hint at a black British identity that would develop more widely three decades later.

“For black Britons working in the entertainment industry offered important opportunities for those that would have been limited in terms of career advancement and social mobility,” says Tackley. “Jazz certainly brought races together, particularly musicians, but also audiences, in a way that was problematic to some degree in this period.”

Synchronicity of sorts finds Rhythm & Reaction connecting with two recent Radio 4 series that both survey British music making just before the jazz age. Clarke Peters (of The Wire) presented three episodes of Black Music In Europe: A Hidden History so looking at the pre-jazz music making of Africans and African Americans in England (and further a field) while Cerys Matthews presented a five-parter on the pioneers of the British recording industry that was taking shape as jazz took hold. While they are both fascinating series to listen to, Rhythm & Reaction allows the viewer to meditate on a great range of objects and build their own associations.

By shining a light on a very British response to a very American musical phenomenon of almost a century ago, Rhythm & Reaction poses plenty of questions for a UK once again divided over identity and outsiders.

Rhythm & Reaction: The Age of Jazz in Britain is at Two Temple Place until the 22 April.